دير مار يوسف الحصن – غوسطا

يَعود سَبَب بناء هذا الدير، كَما يُستفاد من رِسالة وَجَّهَها المطران يوسف اسطفان الأول إلى القاصِد الرسوليّ لويس غوندولفي، إنه لمّا رُسِم يوسف اسطفان، الذي غدا بطريركاً في ما بعد، مطراناً على بيروت، أراد ان يَستقيم في دير عين وَرقَة مع عَمّه المطران يوحنّا، فلَم يرضَ هذا الأخير بإقامة ابن أخيه عِنده، وصار بينهما مُنازعة كبيرة. فتلافياً لهذا الخِلاف بَنى والد المطران يوسف، الخوري جِرجس، في أملاكِه الخاصة، دير مار يوسف الحُصن لولده ليتخِذَه مقرّاً له عِوضاً عن دير عين وَرقَة.

هذا ما ذكرته الرسالة الموما إليها والتي أورد خبرها أنطوان خويري في كتابه "تاريخ غوسطا". ولكنَّ المَعروف عُموماً أن المطران نَفسه بنى هذا الدير بمالِه الخاصّ ومُساعَدة من أبيه الكاهن وإخوته، ومِمّا له من إرث أبيه ماليّاً وعينيّاً، وبعد انتخابه بطريركاً إستمر على السكن فيه.

هذا مع إن قضية تَعَدُّد الأديار التي يقيم فيها البطاركة كانت مَثار اعتراضٍ من الأساقفة الذين كانوا يُطالبون بِمقّرٍ ثابتٍ للبطريركية. ويُذكر أنه عِندما أشرَفَ البطريرك يوسف ضِرغام الخازن على الاحتِضار في العام 1742 اتفق الأساقفة السبعة الحاضرون على مُطالبة البطريرك الجديد بأن يُعيّن لإقامته وإقامة مَن بعده مركزاً بطريركياً ثابتاً. فَطُرحَت هذه القضية من جديد في عَهد البطريرك يوسف اسطفان (1766-1793)، وتحديداً في زمن الأزمة التي وَضَعَت البطريرك في مواجهة الأساقفة. ذلك إن أحد مَطالب الأساقفة في العام 1769 كان يعود إلى مسألة مكان إقامة البطريرك، مُعترضين على إقامَتِه في دير مار يوسف الحُصن ومطالبين إياه بالإقامة في المَقرّ البطريركي في قنّوبين، أو في دير آخر يكون مَقرّاً بطريركياً ثابتاً. كما إنهم كانوا يتهمونه باستخدام مداخيل المَقرّ البطريركي لتوسيع ديره الخاص، ولكنَّ ذلك لم يَمنَع البطريرك يوسف اسطفان من البقاء في دير مار يوسف الحُصن.

وكان البطريرك قد بَنى غُرفةً خاصةً له خارج حرم الدير، وهي المَعروفة باسم "أوضة البَطرك"، كما بنى طابقَين مُلاصقَين للكنيسة يحويان غرفاً لإقامة الراهبات العابدات.. ورَدهات للدَرس والعمل.

وفي هذا الدير عَقَد البطريرك مَجمَعاً للطائفة المارونية سنة 1768 أُقرَّت فيه قوانين تهذيب الإكليروس وتعزيز الدين والنظام البيعي، مِمّا سَوفَ نَتَحدثُ عنه عندما نأتي على سيرة البطريرك يوسف اسطفان والمَجامع التي عقدها.

ويَلفت النظر في هذا الدير، كنيسته التي بُنيت بهِبَة مالية تَلقّاها البطريرك من مَلك فرنسا لويس الخامس عشر وعلى يد بنّائين فرنسيين، فَجاءت رائعةً من روائع الفن والهندسة، خُصوصاً في حَنيَّتها الحجرية الكائنة فوق المذبح الكبير، والتي تعلوها مَنحوتة نُقشَت عليها عِبارة: "يَشرق نجم من يعقوب ويقوم مدبّر من إسرائيل"، وهذه العِبارة نَفسِها مَوجودة في كنيسة عين ورقة-غوسطا بالسِريانية. وقد اعتُبرت هذه الكنيسة من أجمل الكنائس القديمة في لبنان، وأرَّخت لبنائها لوحة رخامية ثُبِّتت فوق عتبة بابها الغربيّ نُقِشَت عليها العبارة التالية:

" هذه الكنيسة قد بُنيت بسعي واهتمام البطريرك يوسف اسطفان، وإحسان لويس الخامس عشر ملك فرنسا، سنة 1769 مسيحية".

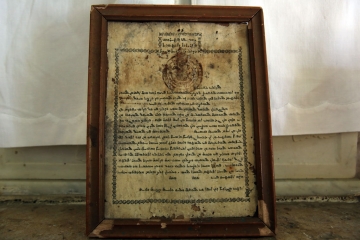

وقد أهدى المَلك شِعارَه المَلكيّ لهذه الكنيسة.. المُعلَّق على جِدارها حتى أيامنا، وهو عِبارة عن درعٍ يرمز إلى المَملَكة الفَرنسية في حينه، حيث نقرأ عليه باللغة اللاتينية مع ترجمتها بالعربية:

"من إحسان المَلك المُظفَّر لويس الخامس عشر سُلطان فرنسا، سنة 1769".

وَيلفِتُنا في الكنيسة أن تيجان أعمدتها الداخلية هي ذوات نقوش مُختلفة غير موحَّدة، لكنَّ كلَّ واحدٍ منها لا يقلُّ جمالاً عن غيره، وسَبَب الاختلاف بينها هو أن كلاً مِنها يرمز إلى حَقَبة مِن حِقب تَطَوّر فن النقش والنحت.

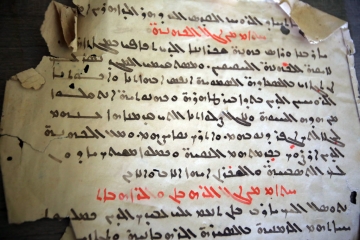

وضِمن تجويفٍ كبير في الجِدار الأيسر تمثال للبطريرك يوسف، يعلو المَثوى الذي يَرقُد فيه، ووراء التِمثال كِتابة باللغة السريانية تعريبها:

"افتح يا لبنان أبوابك التي أُقفلت في وجهي: هذا ما قاله زكريّا لمّا أن شاهَد بالعقل مَحاسِنِك الروحية؛ فقد حسَّنك (حصَّنك) السَيّد بالأسوار المنيعة، أعني مارون ويعقوب ويوحنّا مارون والشهداء الثلاثماية وخمسين وليميناوس ومارينا ودومينينا، وصلاتهم تعضدنا، آمين".

كما يوجَد في الكنيسة، إلى يسار مدخلها، مَدفن يثوي فيه الأميران سليم وسعد الدين، ولدا الأمير يوسف شهاب، وذلك قرب جِرن المَعمودية. وقد دُفن أولهما في العام 1846 والثاني في العام التالي 1847.. كما يُستَدلّ من سِجلّ الوفيات العائد لبلدة غوسطا.

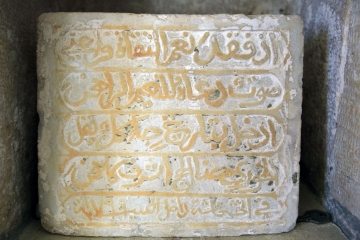

كذلك، في مكان مُنفصل، توجَد مقبرة تَضُمّ رفات أساقفة وكهنة من آل اسطفان الذين يعود هذا الدير لعائلتهم. وأيضاً نَجِد في تجويفٍ في الحائط الخَلفي للكنيسة منحوتة كُتب عليه عبارة:

"إذ فقد نعمة التقاة فراحتي

صوت دعاه للنعيم الراهن

أُدخل بتاريخ جاء كل يقل

الخوري حنا الحاج أشرف كاهن

في الخشخاشة داخل الكنيسة سنة 1799 "،

ووراء هذه اللوحة جُمجُمة لا بُدَّ أن تكون للخوري المُشار إليه.

وتوجد في الكنيسة عِدَّة ذخائر.. بَعضٌ منها موضوع في صندوقٍ زُجاجيّ يحوي عِظاماً بَشرية وقد كُتب عليه اسم "فيكتور" بالأجنبية. وفي صندوقٍ آخر، خشبيّ وصغير، توجد أيضاً بعض العِظام البشرية. وهناك صليب مَعدنيّ، مَجلوب من الفاتيكان، وُضعت في قلبه ذخيرة.

وفوق باب مَدخل الكنيسة، وفوق كُل نافذة من نوافذها الخارجية، نرى الصليب مُرتكزاً على قلب، وهذا الشكل للصليب هو شعار كان مُعتمَداً في منطقة غربي فرنسا حَيثُ نَجِد الصليب المُرتكز على القلب مع عبارة: "لله والملك"، وربما كان وجود هذا الشعار في الكنيسة بمثابة عربون شكرٍ لملك فرنسا، لويس الخامس عشر، كما ذكرنا سابقاً.

وتعلو الكنيسة من الخارج قِبَّة الجرس التي نُقشت عليها العبارة التالية: "بنى هذه القبة المُعلّمان يوسف وحبيب مناسا بمال كرام آل اسطفان الغوسطاويين".

ساكن دير مار يوسف الحُصن البطريرك يوسف اسطفان (1766 – 1793)

ابن بلدة غوسطا، وُلد فيها عام 1729. سَليل عائلة أطلعت الكثيرين من رجال الدين: المطارنة جِرجس ويوحنّا وبولس ويوسف الأول ويوسف الثاني، والمونسنيور خيرالله الشهير في أميركا، وتوَّجت عطاءها بالبطريرك يوسف، موضوع حديثنا، والمعروف باسم يوسف السادس.

جرى انتخابه بطريركاً في دير مار شلّيطا مقبس في 9 حزيران 1766، واختار أولاً الإقامة في دير قَنّوبين، ولَكِنه إضطر إلى تَركِه بَعدَ مُدة لأسباب سياسية وأمنية، فانتقل إلى دير مار يوسف الحُصن، عائداً إلى الدير الذي بناه، وإلى البلدة التي هي مَسقِط رأسه.

وقد شَكَّل هذا البطريرك ظاهرةً فريدةً في تاريخ الكنيسة عامَّةً، بِصعوده المُبكّر والسريع إلى السُلطة الكنَسية الأولى في طائفته. وقد إستَحقَّ ذلك بذكائه وفضائله، فكان من أصغر البطاركة الموارنة سِنّاً لدى انتخابه إذ كان في السابعة والثلاثين من عِمره، كما كان قد ارتقى إلى الدرجة اللأسقفية في عمر الخمسة وعشرين عاماً.

ومن مَظاهِر غيرتِه وتَقواه إنه أوقف دير عين وَرَقة الذي هو أيضاً ملك عائلته آل اسطفان، لتحويله إلى مدرسة كانت الأولى في لبنان، مُضحّياً هكذا بحقّ العائلة الشرعيّ على هذا الدير، ومُقنعاً أبناءها بأن خِدمة العِلم والجيل الناشىء تتقدَّم على المصلحة الشخصية. وبالفِعِل أدَّت هذه المدرسة خَدماتٍ عِلمية جليلة، وليس أدَلّ على ذلك من أن البطريرك يوسف حبيش (1823-1845)، والمُعلِّم بطرس البستاني صاحب "دائرة المعارف اللبنانية"، والأديب فارس الشدياق أحد كبار أعلام عصر النهضة، والمطران يوسف الدبس صاحب "تاريخ سوريا" ومؤسس مدرسة "الحكمة" في بيروت، كانوا من تلامذتها.

والبطريرك هو نفسه كان من العلماء الأعلام، لذلك لُقِّب بـ "مِلفان الكنيسة المارونية"، وله مؤلفات عدَّة باللغات العربية والسريانية واللاتينية والإيطالية في المواضيع الدينية والطقسية والفلسفية والتربوية.

ومن مُنجزاته عَمَلُهُ على تطبيق أحكام "المَجمَع اللبناني"، ولتَحقيق هذا الهدف عَقَد ثلاثة مَجامِع هي مَجمَع دير مار يوسف الحُصن في غوسطا، ومَجمَع كنيسة السيّدة في عين شقَيق التابعة لقرية وطى الجوز- كسروان، وأخيراً مَجمَع دير سيّدة بكركي.

مَجمَع غوسطا: عُقد ما بين 16 و 30 أيلول من العام 1768 برئاسته، وبحث في قضية الرهبان مُرغِماً إياهم على الخضوع المُطلق للبطريرك والمطارنة، ومَنعهم من مُمارسة خِدمة الرعايا، تطبيقاً لمُقررات "المَجمَع اللبناني"، وأكد على واجب كل ماروني ان يقبل بمقررات هذا المَجمَع.

مَجمَع عين شقَيق في وطى الجوز: عُقد من 6 إلى 11 ايلول 1786 برئاسته ايضاً، وأُعلن فيه القبول بقرار البابا بيوس السادس (1775-1799) الداعي إلى إعادة البطريرك إلى منصبه الذي كان قد نُحّي عنه لأسباب سنتحدَّث عنها لاحقاً، كما ذكَّر هذا المَجمَع بتقسيم الأبرشيات وتحديدها، وألزم المطارنة بالسَكن قريباً من البطريرك، مُلغياً بذلك القانون القاضي بوجوب سكن المطارنة في أبرشياتهم.

مَجمَع بكركي الأول: وقد دام من 13 إلى 16 كانون الأول 1790، وترأسه القاصِد الرسولي المطران جرمانوس آدم والبطريرك يوسف اسطفان، فأكَّد كسابِقه على تَقسيم الأبرشيات وتحديدها، وعلى حَق البطريرك والمطارنة وحدهم بانتخاب مطارنة جُدُد، وعلى وجوب سِكن المطارنة في أبرشياتهم.. خلافاً لقرار مَجمَع عين شْقَيِقْ الذي أوجب سَكَن المطارنة بقُرب البطريرك، كذلك أكد على وجوب فَصل أديار الرهبان عن أديار الراهبات.

ومن مُنجَزات هذا البطريرك كذلك انفتاحَه على دول الغرب، وإقامة صِلاتٍ معها، وكان من نتيجة مساعيه الحصول من المَلِك لويس الخامس عشر على تجديد الحِماية الفرنسية للأمَّة المارونية.

ولكن لمّا كان، تِبعاً لقول المَثل، كل ذي نعمةٍ مَحسود، فإن هذا البطريرك اللامِع والمُتميّز تَعرَّض لمؤامرات مُبغِضيه من الإكليروس الذين كانوا على خلافٍ معه ولم يَرُقهم وصوله بدلاً مِنهم إلى السدَّة البطريركية، وساعدهم في ذلك بروز ظاهرة الراهبة هِندية وما أثارت من تأييد لها في بعض الأوساط وشكوك حولها في أوساطٍ اخرى.

وكان من بين الذين عَطَفوا عليها البطريرك يوسف اسطفان، الذي لم يَلحُظ عليها أيَّ حيادٍ عن تعاليم الكنيسة، فلم يَجِد حَرَجاً في مُساعدتها وتشجيعها. ولكن بدأت الشائعات تُنسَج حولها من أنها تَزعَم كونها مُلهَمةً وتُبصِّر رؤىً سماوية تَتَّحد فيها بالمسيح، وهو ما إذا كان صحيحاً فلا يعدو ان يكون وهماً تتوهَّمه لأنها كانت تُبدي من ضروب العِبادة والإغراق في التأمل والصلاة ومناجاة الله، ما يُضفي عليها مِسحةً من القداسة. ولكن لا شَك في إن ذلك بولِغ فيه من جانِب أعداء البطريرك اسطفان الذين وجدوا في انحيازه إلى هذه الراهبة مَمسَكاً يَستَغلّونه ضِدَّه، وفي طليعتهم المطران ميخائيل الخازن الذي كان يطمَح إلى اعتلاء الكرسيّ البطريركي.. ففاته ذلك لمصلحة البطريرك اسطفان.

ولم يكن هذا المطران، في الواقع، وَحدَه في مُناصبة البطريرك العداء، فقد تَشَكَّلت مَجموعَة من مُستغلّي قضية هِندية ليطالوا عن طريقها البطريرك.. مؤلفة من القاصِد الرسولي الأب دو موريتّا، والمطران ميخائيل فاضل، والقَس سِمعان السِمعاني، والأب أرسانيوس دياب والمطران الخازن، حتى إن السِمعاني ودياب ملآ الدنيا صِياحاً، وأرسَلا الرسائل والتقارير إلى رومية مُتَضَمِنةً أشياء لا يُصَدّقها عاقل، فَتَدحَضُها الوقائع ويتبيَّن أنها ثمرة تَحامُل على البطريرك.

والواقع إن البطريرك اسطفان لم يَكُن، كما أشرنا، أول مَن عَطَف من الإكليروس الماروني على الراهبة هِندية ولا الوحيد في ذلك، فقد سَبَقه بطاركة ومطارنة وكهنة وفريق من الشعب. ويَظهر هذا من كلامِه، إذ قال إنه لم يجرِ في ذلك إلا على خُطى أسلافه، كما يَظهر من قول الأب لويس صفير، في كتابه عن البطريرك يوسف التيّان، إن الكرسيّ الرسوليّ نفسه اضطَرّ إلى التدخُل تارةً لتأييدها وإطرائها وطوراً لشَجبِ عَملِها وإدانته، وإنه وَبَّخ بطاركةً ومطارنةً وكهنة، او عَلَّق مُمارسَتِهم لسلطانهم وواجباتهم، مِمّا يَدلُّ على أن البطريرك يوسف اسطفان لم يَتفرَّد في مَوقِفِه هذا ولم يَكن بادع بدعةٍ فيه، بل كان هناك من قَبْله جوُّ عام يسود فريقاً كبيراً من الإكليروس الماروني والشعب في تصديقهم لهذه الراهبة وإيمانهم بِتَقواها وقداستها، وعلى رأسهم بطاركة سبقوا البطريرك اسطفان في إعتلائهم السِدَّة البطريركية وعَطفِهم على هِندية.

ولكن لمّا كان البطريرك يوسف اسطفان من أشَدّ المُناصرين للراهبة هِندية، فَقَد راح مُناؤوه وأخصامِه يوغرون صَدرَ الأمير عليهما، وأغروا مَجمَع نشر الإيمان ضِدَهُما بالشكاوى التي رفعوها إليه، واتهامهم الراهبة المذكورة بأنها ضالَّة عن سِراط الإيمان والعقيدة، كما أتهموا البطريرك بالانحراف في مجرى هذا الضِلال. فلمّا وَصَلت إلى رومية جميع التقارير والرسائل التي كَتَبها أضداد البطريرك أصدر الكرسيّ الرسوليّ قراراً بالغاء رهبانية هِندية سنة 1779، كما أصدر قراراً بِمنع البطريرك يوسف اسطفان من مُمارسة سُلطاته البطريركية والأسقفية، تاركاً له حَق التَصَرُّف بالدرجة الكهنوتية وَحدَها، وَعيَّن المطران ميخائيل الخازن نائباً بطريركياً، مفوِّضاً إليه كامل السلطان البطريركي ما عدا انتخاب الاساقفة وسيامتهم، وآمراً جميع الموارنة بإطاعته والخضوع له.

وقد استدعي البطريرك إلى رومية لتَبرِئَة نفسه أمام البابا بيوس السادس (١٧٧٥ - ١٧٩٩)، ولكنَّ حالتَه الصِحية لم تَسمح له بِمُتابعة رحلته، فتوقَّف في دير الكَرمِل في فلسطين في العام 1780 ، وأرسل قُصّاداً من قِبَله إلى الأعتاب الرسولية حاملين رسائل وبيّنات تُثبِت بالبراهين السَديدة صِدق طاعة سَيّدهم وحقيقة مَرَضِه، وقد ناضلوا هناك نِضالاً نَشيطاً أدّى إلى وضوح الحقيقة للبابا بيوس السادس (١٧٧٥ - ١٧٩٩) والمَجمَع المُقدَّس وبِطلان المَزاعِم التي نُسِجَت عن البطريرك، فَساهَم هؤلاء القُصّاد، والرسائل التي حَملوها مِنه، في إسقاط المَنِع الذي صدر بِحقّه عن مُمارسَة سُلطاته البطريركية وإعادته إلى مركزه، وذلك في العام 1785.

أجل، عاد البطريرك يوسف اسطفان إلى سِدَّته البطريركية مُعظَّماً مُكرَّماً، مُطلقاً صَرخته الشهيرة: "افتح يا لبنان أبوابك التي سُدَّت في وجهي"، فاستقبله أهالي كسروان بالإحتفالات والأهازيج، وأوصلوه إلى مَقرَّه البطريركيّ الذي غَصَّ بالمُهنئين، فعادت مَعه الحياة إلى الدير. واستأنف عَمَله الكنسيّ والاصلاحيّ والثقافيّ والتربويّ والإجتماعيّ مُحدِثاً نَهضةً شاملة في الطائفة، وتوفّي في 22 نيسان سنة 1793، فَدُفن في كنيسة دَيره، دير مار يوسف الحُصن – غوسطا.

أمّا في ما خَصَّ الراهبة هِندية، واسمها الأصليّ حَنّة العجيمي، فيوضِح أمرها الأب لويس صفير في كتابه: "البطريرك يوسف التيّان" بقوله إنها "راهبة مارونية وُلدت في حلب يوم 6 آب 1720، وأقامت في لبنان مُحْدِثةً في الكنيسة المارونية إضطراباً ما يُقارب النِصفَ قرنٍ من الزمن، وذلك بروحانيتها وقداستها اللتين ما زالتا مَوضِع شَكٍ حتى الآن. فاضطرَّ الكرسيّ الرسوليّ إلى التدخل في عدة مُناسبات تارةً لتأييدها وإطرائها وطوراً لشَجب عملها وإدانته، كما وبَّخ بطاركةً ومطارنةً وكهنة، او علَّق مُمارَسَتِهم لسُلطانهم الحبريّ أو واجباتهم الكهنوتية.. كما ذكرنا سابقاً.

وأما هِندية فنُقلت في نهاية المَطاف إلي دير سيّدة الحقلة بَعدَ أن تَدَخَّل البطريرك يوسف التيّان شخصياً بتوجُّهه إلى عينطورة، حيث كانت تُقيم هِندية مع الجاماتي وكيلها، وإجبارها على الانتقال إلى دير سيّدة الحقلة في دلبتا والاستقرار فيه، مانعاً إياها من الإتصال بأي شخصٍ خارج هذا الدير، حَيثُ ماتَت في 13 شباط 1798 ودُفِنَت هناك. وهكذا انتهت مسألة هِندية، ولَكِنَّ، من الناحية التاريخية واللاهوتية والنقدية، تبقى مَسألتها قِصةً روائية تَشغَل الخيال...

يُذكر بأن البطريرك يوسف اسطفان هو كاتب، ومن أشهر التراتيل التي كتبها: ارسل الله، يا شعبي وصاحبي، سبحان الكلمة وغيرها...

Monastery of St. Joseph Al-Hosn – Ghosta

The reason behind the construction of this monastery, as can be read in a letter addressed by Archbishop Youssef Estephan I to the Apostolic Nuncio, Louis Gandolfi, is that when Youssef Estephan, who later became a patriarch, was ordained Metropolitan of Beirut, he wanted to live in the monastery of Ain Warqa with his uncle, Bishop Youhanna. The latter was not satisfied with this cohabitation, and a great dispute arose between them. To quell the dispute, the father of Archbishop Youssef, Father Gerges, built the monastery of St. Youssef al-Hosn on this property, for his son to turn into his headquarters, instead of the monastery of Ain Warqa.

This episode was mentioned in the letter attributed to him, which was reported by Professor Antoine Khoueiri in his book "The History of Ghosta". However, it is generally agreed on that the Metropolitan himself built this monastery with his own money and with the help of his father the priest, and his brothers, and used his father’s inheritance to do so, and, after he was elected patriarch, continued to live in it.

This is even though the issue of the multiple monasteries in which the patriarchs reside had been brought up by the bishops who were demanding a fixed seat for the patriarchate. It is mentioned that when Patriarch Youssef Dargham al-Khazen was dying in 1742, the seven bishops present agreed to ask the new patriarch to appoint a permanent location for his residence and the establishment of a permanent patriarchal office after him. This issue was raised again during the reign of Patriarch Youssef Estephan (1766-1793), specifically at a time of crisis that pitted the patriarch against the bishops. This is because, in 1769, the bishops objected to the residence of the patriarch in the monastery of St. Joseph Al-Hosn and asked him to reside in the patriarchal headquarters in Qannoubine, or in another monastery that would be a permanent patriarchal seat. They were also accusing him of using the revenues of the patriarchal headquarters to expand his private monastery, but that did not prevent Patriarch Youssef Estephan from staying in the monastery of St. Joseph Al-Hosn.

The patriarch had built a special room for him outside the monastery precincts, known as “the patriarch’s quarters.” He also built two floors adjacent to the church containing rooms for the residence of the nuns, and halls for study and work.

In this monastery, the Patriarch held a Synod for the Maronite community in 1768, in which the laws of disciplining the clergy, promoting religion, and the sales system were approved, and we will talk about all of this when we get to the biography of Patriarch Youssef Stephen and the councils he held.

The most intriguing edifice in the monastery is its church, which was built with a financial donation received by the Patriarch from King Louis XV of France and at the hands of French builders. It was a marvelous masterpiece of art and engineering, especially in its stone apse located above the great altar, which is topped with a carving inscribed with the words: “A star will rise from Jacob, and a ruler will arise from Israel.” This same phrase is found in the Church of Ain Waraka-Ghosta in Syriac. This church was considered one of the most beautiful ancient churches in Lebanon, and a marble plaque was dated for its construction. It was installed above the threshold of its western door, on which the following phrase was engraved: “This church was built with the efforts and care of Patriarch Youssef Estephan and the generous donation of Louis XV, King of France, in the Christian year 1769.”

The king gifted his royal emblem to this church, and it still hangs on its wall until our days. It is a shield symbolizing the French kingdom at the time, where we read it in Latin with its translation in Arabic: “With the generosity of Louis XV, the glorious King of France, 1769.”

In the church, we notice that the crowns of its inner columns have different inscriptions that are not uniform, but each one of them is no less beautiful than the others, and the reason for the difference between them is that each one of them symbolizes an era of the development of the art of engraving and sculpture.

Within a large cavity in the left wall, is a statue of Patriarch Joseph, above his final resting place, and behind the statue can be seen a writing in the Syriac language which translates into: “Open, O Lebanon, your doors: This is what Zacharias said when he saw with his mind your spiritual virtues; The Lord has surrounded you with impenetrable walls. May Maron, Jacob, John Maron, the three hundred and fifty martyrs, Limenaeus, Marina, and Domenina, pray for us. Amen.”

In the church can also be found, to the left of its entrance, a tomb in which the Emirs Salim and Saad al-Din, two sons of the Emir Youssef Chehab, rest, near the baptismal font. The first of them was buried in 1846 and the second in 1847, as is indicated in the death register of the town of Ghosta.

In a separate location, can be found a tomb containing the remains of bishops and priests from the Estephan family, to which this monastery belongs.

We also find in a carved cavity in the back wall of the church which contains a skull that must have belonged to Father Hanna al-Hajj.

There are several relics in the church. Some of them are placed in a glass box containing human bones, on which the name “Victor” is written in a foreign language. In another box, wooden and small, there are also some human bones. There is also a metal cross, brought from the Vatican, which contains a small relic as well.

Above the entrance door of the church, and above each of its windows, we see the cross resting on a heart, and this shape of the cross is a motto that was adopted in the western region of France, where we find the cross centered on the heart with the phrase: “To God and the King.” Perhaps the presence of this emblem in the church was a token of appreciation to the King of France, Louis XV who contributed to the construction of the church, as we mentioned earlier.

The church is topped with a bell dome, and, on the bell, the following phrase is inscribed: “This dome was built by the two masters Yousuf and Habib Menassa with a donation from the honorable Estephan family, from Ghosta.”

The inhabitant of the monastery of Mar Youssef Al-Hosn, Patriarch Youssef Estephan (1766-1793 .)

He was born in the town of Ghosta, in 1729. He comes from a family that includes many members of the clergy: Metropolitans Gerges, John, Paul, Joseph I and Joseph II, and Monsignor Khairallah, who is famous in America. The dedication of this family to monastic life culminated with Patriarch Youssef, the subject of our conversation, known as Joseph VI.

He was elected patriarch in the monastery of St. Shalita Moqbes on June 9, 1766, and first chose to reside in the monastery of Qannoubine, but he was forced to leave it after a while for political and security reasons. So, he moved back to the monastery that he had built in his hometown, the monastery of Saint Joseph al-Hosn.

This patriarch’s rise constituted a unique phenomenon in the history of the Church in general, with his early and rapid rise to become the first ecclesiastical authority in his sect. His intelligence and virtues made him one of the youngest Maronite patriarchs at the time of his election when he was thirty-seven years old, and he had been elevated to episcopal rank at the age of twenty-five years.

An indicator of his zeal and piety is that he converted the monastery of Ain Warqa, which is also the property of his family, the Estephan family, into the first school in Lebanon, thus sacrificing the family’s legal right to this monastery, and convincing its heirs that serving science and the emerging generation takes precedence over personal interest. Indeed, this school was dedicated to the service of science and knowledge, as is evidenced by the fact that the teacher Boutros Al-Bustani, the owner of the “Lebanese Department of Knowledge,” the writer Faris Al-Shidyaq, one of the great figures of the Renaissance, and Bishop Youssef Al-Debs, the author of “Syria’s History” and the founder of “Al-Hikma” school in Beirut, were all its students.

The Patriarch himself was one of its most well-known scholars, and he was called the "Doctor of the Maronite Church", and he has written several books in the Arabic, Syriac, Latin and Italian languages on religious, ritual, philosophical and educational topics.

Among his achievements is his work on implementing the provisions of the “Lebanese Synod.” To achieve this goal, three councils were convened: the Synod of Saint Joseph Al-Hosn Monastery in Ghosta, the Church of Our Lady in Ain Shaqiq in the village of Wata Al-Joz, and finally the Synod of the Monastery of Our Lady of Bkerki.

The Synod of Ghosta: Held between September 16 and 30 of the year 1768 under his presidency, and discussed the issue of monks, compelling them to absolute submission to the patriarch and metropolitans, and preventing them from exercising parish service in application of the decisions of the “Lebanese Synod.” It emphasized the duty of every Maronite to accept the decisions of this Synod.

The Synod of Ain Shaqiq in Wata al-Jawz: Held from 6 to 11 September 1786 under his presidency, and announced the acceptance of the decision of Pope Pius VI (1775-1799) calling for the return of the patriarch to his position from which he had been dismissed for reasons that we will talk about later. The dioceses were defined and specified, and the metropolitans were obliged to live close to the patriarch, thus repealing the law stipulating that metropolitans must reside in their dioceses.

The First Synod of Bkerki: It lasted from December 13 to 16, 1790, and was presided over by the Apostolic Nuncio, Bishop Germanos Adam, and Patriarch Youssef Estephan. It also emphasized the division and identification of dioceses, and the right of the patriarch and metropolitans alone to elect new metropolitans, and the necessity of metropolitans residing in their parishes, contrary to the decision of the Ain Shaqiq synod, which required the metropolitans to reside near the patriarch. It also emphasized the necessity of separating the monasteries of the monks from the monasteries of the nuns.

Among the achievements of this patriarch was his openness to Western countries and establishing contacts with them, and as a result of his efforts to obtain from King Louis XV the renewal of the French protection of the Maronite nation.

But because, as the proverb says, everyone who is blessed is envied, this brilliant and distinguished patriarch was subjected to the conspiracies of members of the clergy who were at odds with him, and who coveted his position. They also relied on the emergence of the phenomenon of Mother Hindia who aroused both support and doubt in different circles.

Among those who sympathized with her was Patriarch Youssef Estephan, who did not notice any deviation from the teachings of the Church, and did not object to her assistance and encouragement. But rumors began to be woven around her, saying that she claims to be inspired by heavenly visions in which she is united with Christ, which, if it were to be true, could be nothing more than an illusion resulting from worship and immersion in meditation, prayer, and dialogues with God, which would give her a tinge of holiness. But there is no doubt that the enemies of Patriarch Estephan, who found that in his alignment with this nun, he was being held captive and exploited against his own will, were exaggerating, with at their forefront Archbishop Michael El-Khazen, who aspired to ascend the patriarchal chair himself.

This metropolitan was not alone in his hostility against the patriarch. A group of people who took advantage of the phenomenon of Mother Hindia took a position against him, including the Apostolic Nuncio, Father de Moretta, Archbishop Michael Fadel, Reverend Samaan Al-Samani, Father Arsanios Diab, and Archbishop Al-Khazen. Al-Samani and Diab expressed their discontent loudly and clearly, and sent letters and reports to Rome, including accounts that a sane person would not believe. The facts refuted them, and it was found that their claims were the fruit of prejudice against the Patriarch.

In fact, Patriarch Estephan was not, as we mentioned, the first to show sympathy for Mother Hindia, nor was he the only one to do that. He was preceded by patriarchs, metropolitans, priests, and civilians. This is evident from his words, as he said that he only followed in the footsteps of his predecessors, as Father Louis Sfeir mentions in his book on Patriarch Youssef Al-Tian. Because the Holy See himself had to intervene at times to support and praise her and at other times to denounce and condemn her, and because he reprimanded patriarchs, metropolitans, and priests, or suspended the exercise of their authority and duties, it was clear that Patriarch Youssef Estephan was not unique in this position and wasn’t the first to adopt it. Rather, there was a general atmosphere before him that prevailed over a large group of Maronite clergy and people in their belief in this nun and their belief in her piety and sanctity, including patriarchs who had preceded Patriarch Estephan.

However, the patriarch’s enemies took advantage of his position to pit the Congregation for to Propagation of the Faith against him, When all the reports and letters written by the patriarch’s opponents reached Rome, the Holy See issued a decree abolishing the order of Mother Hindia in 1779. It also issued a decree banning Patriarch Youssef Estephan from exercising his patriarchal and episcopal powers, leaving him the right to only remain a priest, and he appointed Archbishop Michael Khazen as a deputy patriarch and gave him full patriarchal authority except for the power to elect and ordain bishops, and he commanded all Maronites to obey him and submit to him.

The Patriarch was summoned to Rome to acquit himself before Pope Pius VI (1775-1799), but his health condition did not allow him to complete his journey He stopped in the Carmel monastery in Palestine in 1780, and sent an instead of himself representatives bearing letters and evidence of the sincerity of his obedience and the reality of his illnesses. There they actively sought to the clarity of the truth to Pope Pius VI (1775-1799) and the Holy Council and to prove the invalidity of the allegations made about the patriarch, and they successfully manage to restore him to his position, in 1785.

Yes, Patriarch Youssef Estephan returned to his patriarchal seat with all due honors, famously saying: "O Lebanon, open your doors that were closed to me." The people of Kesrouan greeted him with celebrations and chants and brought him to his patriarchal residence, which was filled with well-wishers. He resumed his ecclesiastical, reform, cultural, educational, and social work, bringing about a comprehensive renaissance in the sect. He died on April 22, 1793, and was buried in the church of his monastery, the monastery of St. Joseph Al-Hosn - Ghosta.

As for Mother Hindia, whose original name is Hanna Al-Ajimi, Father Louis Sfeir explains in his book: “Patriarch Youssef Al-Tayan” by saying that she is “a Maronite nun who was born in Aleppo on August 6, 1720. She moved to Lebanon, where she caused turmoil in the Maronite Church for nearly half a century, due to her spirituality and sanctity, which are still questionable until now. The Holy See was forced to intervene on several occasions, sometimes to support and praise her, and sometimes to denounce and condemn her. He also sometimes reprimanded patriarchs, metropolitans, and priests, or suspended the exercise of their authority and duties, as we previously mentioned.

Mother Hindia was eventually transferred to the Monastery of Our Lady of the Field after Patriarch Youssef Al-Tian personally intervened by heading to Aintoura, where Hindia was staying and forcing her to move to the Monastery of Our Lady of the Field and settling there, preventing her from communicating with anyone outside this monastery. She died on February 13, 1798, and was buried there. Thus ended her story but, historically, theologically, and critically, it remains a fictional story that engages the imagination.

It is noted that Patriarch Youssef Estephan was a writer, and among the most famous hymns he wrote are: Arsal Allah (God Sent), Ya Shaabi wa Sahibi (O My People and My Companion), Subhan Al-Kalima (Glory to the Word), and others.